What are the Passion Narratives?

All four Gospels contain an account of the passion of Jesus – a narrative which describe the events leading up to and including this crucifixion. There are similarities across each of these narrative, but like any event described by different authors, each account contains unique perspectives and emphasises different aspects.

While the Passion Narratives retell the final week of Jesus’ life they were not written as a report of what occurred. Rather, the challenge for each of the Gospel writers was to explain the purpose of Jesus’ life, a life which culminated in death: in short, who was Jesus in his death? And what did the unceremonious death mean for any who might follow? Focused on the religious significance of his death, particularly the links to Psalms 22, 31, and Isaiah 52-53, each of the Gospel writers filtered their description through the questions and concerns of their community, thus flavouring their writing with the needs of those they knew best.

Old Testament links

Psalm 22 contains a striking parallel to the events of Jesus’ passion for Mark and Matthew. Jesus himself speaks the opening words of the Psalm on the cross, saying, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34 and Matthew 27:46).

In Psalm 31 the psalmist includes expressions of trust in God in the face of adversity… “But I trust in you, O Lord; I say, “You are my God” (Psalm 31:14). Luke draws on this for his community, as with his final breath Jesus says, “Father, into your hands I commend my Spirit” (Luke 23:46).

Isaiah 52:13-53:12 is often called the Servant song. These passages describe a suffering servant who does so willingly for others. The Gospel narratives describe Jesus as the fulfillment of this, noting his death and resurrection as part of God’s plan for salvation.

The Gospel writers went beyond simply recounting the details of Jesus’ death. They sought to explain its purpose and meaning to a particular group with particular questions by linking it to the promises of the Hebrew Scriptures.

These links to Hebrew Scriptures indicate that Jesus’ death was part of God’s eternal plan to which Jesus freely committed himself.

The Gospel writers recognised the need to highlight the purpose of Jesus’ death and its connection to God’s eternal plan. They drew links between Jesus’ suffering and the Hebrew Scriptures, particularly the prophetic passages in Psalms and Isaiah. This served to emphasise that Jesus’ death was not a random but rather a fulfilment of God’s plan.

The Gospels

Matthew

Matthew’s whole Gospel focuses on the fulfilment of Old Testament prophecies in the passion narrative. In the passion Matthew highlights as Messiah for whom Judaism has yearned and waited. The suffering of Jesus is the suffering of the Israelites.

Mark

Mark’s Gospel presents a fast-paced and concise account of the passion. Most likely written for a community sought by a persecuting emperor, Mark emphasises Jesus’ own suffering: as his community face a horrible death, so does Jesus.

Luke

Luke’s whole Gospel highlights Jesus’ compassion and forgiveness. Luke’s determination to show Jesus as the one who welcomes all comes through in Jesus’ words of forgiveness as he dies.

John

John’s Gospel provides a distinct theological perspective on the passion, focusing on Jesus’ divine nature and his purpose in fulfilling God’s plan of salvation. Jesus final words, ‘It is finished’, sum up the view of John.

“Matthew emphasises Jesus as the fulfiller of Old Testament prophecies, Mark emphasises Jesus’ abandonment and the scandal of the cross, Luke emphasises Jesus’ compassion, and John emphasises Jesus’ sovereignty and control over events.”

R. E. Brown, The Death of the Messiah

World of the Text

Characters & Setting

Below is an outline of the characters who appear across all Gospels:

Jesus: The central character, portrayed as the Son of God and the Messiah, who undergoes betrayal, arrest, trial, crucifixion, and resurrection.

Disciples: The followers of Jesus, his students, including Peter, James, John, Judas and Mary Magdalene, all of whom play significant roles in the narrative.

Jewish Religious Leaders: Chief priests, scribes, and Pharisees who oppose Jesus and play a crucial role in his arrest and religious trial. In Matthew and John’s Gospel an antisemitic tone is evident in the way these characters are portrayed so be careful. It is almost certainly not an accurate view of the leaders at the time, but a more hostile view, reflective of the period in which these Gospel were written, and transferred back into the description of the passion. Watch for Matthew’s blood curse in particular, where the Jews accept responsibility for the death of Jesus (m 27:25). It has been responsible for much anti-Jewish sentiment and teaching.

Judas Iscariot: The disciple who betrays Jesus, leading to his arrest.

Pontius Pilate: The Roman governor who presided over Jesus’ trial and ultimately orders his crucifixion. Only a Roman could order death by crucifixion. Luke will suggest the Pilate was less than comfortable with Jesus’ crucifixion, a possible nod to his intention to appeal to those in a Roman world.

Soldiers: Roman soldiers involved in the crucifixion and mocking of Jesus. Matthew will say that soldiers were placed on guard at the tomb to stop Jesus’ body being stolen.

The Crowd: a mixture of supporters and opponents of Jesus. In Matthew’s Gospel their influence is heightened.

The Passion narratives take place in Jerusalem, specifically in the Garden of Gethsemane, the high priest Caiaphas’ house, Pilate’s judgment hall, and Golgotha (the place of crucifixion). Jesus was crucified at Golgotha, meaning “place of the skull” (Mk 15:22) and buried in a nearby tomb (Jn 19:41). It may have been a place used regularly for executions (hence the grim name) or it may have resembled a skull in some way. It is not described in the Bible as a hill. The exact location of the crucifixion is disputed. Due to ritual defilement and uncleanness, no tombs were ever inside a city’s wall.

Ideas/Phrases/Concepts

Betrayal: Judas’ act of betrayal by handing Jesus over to the religious authorities.

“Then one of the Twelve – the one called Judas Iscariot – went to the chief priests and asked, ‘What are you willing to give me if I deliver him over to you?’ So they counted out for him thirty pieces of silver.” (Matthew 26:14-15)

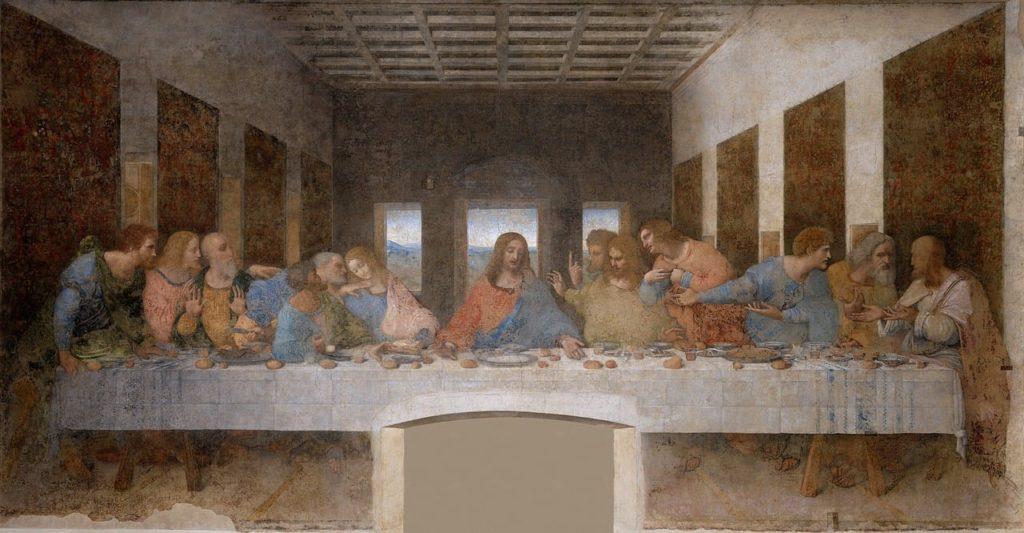

Last Supper: The final meal shared by Jesus and his disciples, during which Jesus institutes the Eucharist.

Arrest and Trial: The arrest of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane and his subsequent trials before Jewish and Roman authorities. Watch how the charge against Jesus changes – from a religious one, blasphemy, to a political one, in effect treason (King of the Jews).

Peter’s Denial: Peter’s denial of Jesus three times before his crucifixion.

“But he denied it before them all. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about,’ he said. Then he went out to the gateway, where another servant girl saw him and said to the people there, ‘This fellow was with Jesus of Nazareth'” (Matthew 26:70-71).

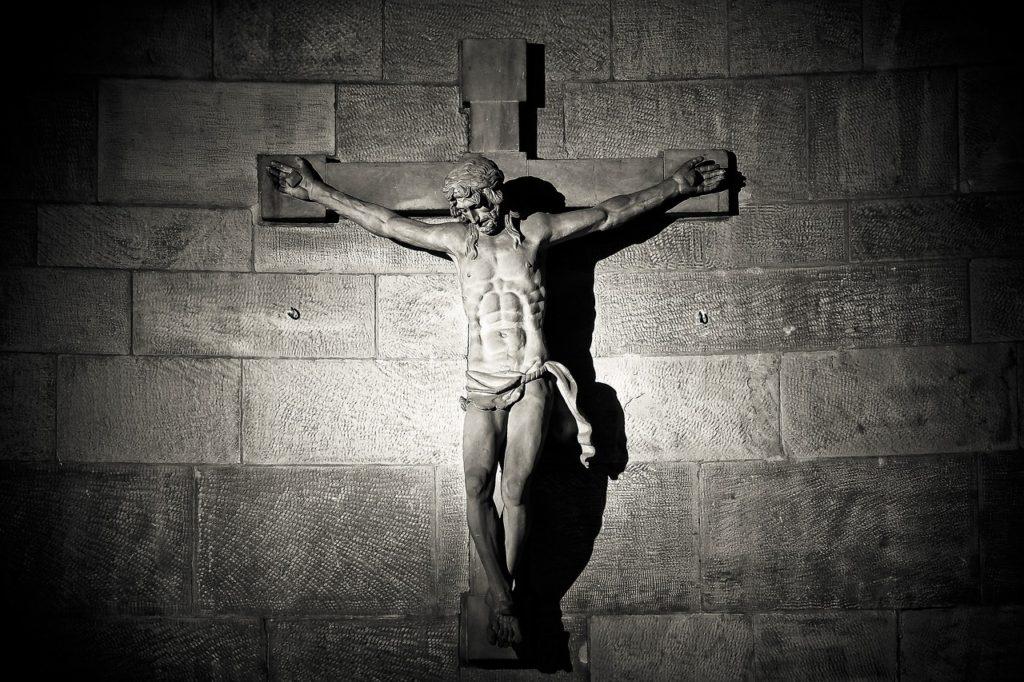

Crucifixion and Death: The crucifixion of Jesus on the cross and the events surrounding his death.

Crucifixion was a public reality for people in the Roman Empire and used as a form of punishment for murder, rebellion, treason, military desertion, and robbery. Crucifixion was one of the most barbaric forms of execution – usually reserved for the lowest classes, slaves, foreigners, and political rebels. It was aimed to intimidate anyone who could disrupt the status quo, symbolising the supremacy of the Roman government over the victims and anyone who might try and emulate them. Jesus was crucified as a form of political sedation, although claiming to be the Messiah was in itself not a crime.

The Romans did not invent crucifixion – they adopted it from the Persians, Assyrians, and Jews. For Jews it seemed even worse; because the victim was hung naked this reflects understanding in Deuteronomy that anyone hanging ‘on a tree’ was under God’s curse (Deut 21:22-23).

Crucifixion was painful, demeaning, and public. It would first torment and then whip, stab, or burn (or all three) the condemned person. Jewish law restricted whipping to 40 lashes, but Roman law had no such limits. Soldiers would make a wooden placard (titulus) listing the alleged charges and hang it around the victim’s neck as a way of publicly humiliating them for their crimes. The soldiers would then force the victim to carry a wooden cross beam (patibulum), weighing 16 to 20kg over their shoulders, parading them through the streets to ensure maximum recognition and humiliation. Victims would only be allowed assistance if they were extremely weak and were likely to collapse before the crucifixion could be carried out. The victims and spectators would move to some public space where there was already an upright fixed in place. Nails were typically hammered through the forearms. Then, because of the weight of the body, they would tear through the flesh until they reached the wrist. The victims may be seated onto a small ledge that would support their weight, relieve pressure on their arms, and hence delay death. The legs would be attached with ropes or nailed to the pole on either side or through both feet. The person would be perched there, close to the ground, and within striking distance of wild animals and passers-by. They would be stripped of clothes and valuables, leaving them exposed to the elements.

Causes of death could vary. The Gospel accounts are quite restrained and unemotional in their depiction of the crucifixion. For example, they make no mention of the fact that Jesus was almost certainly hung naked on the cross, hinting at it by the soldiers casting lots for his clothing (v. 34).

Resurrection: The resurrection of Jesus three days after his death.

Salvation: For a simple explanation please see the glossary.

Jesus teaches that salvation was and is always a gift from God: people cannot save themselves – their readiness to trust God allows them to be open to God’s saving action. In this sense, Jesus cannot save himself. Salvation is God’s response to Jesus’ faithfulness and integrity.

Honour and shame:

The core values of honour and shame were central to Mediterranean society. During Jesus’ lifetime, no opponent successfully ‘shamed’ him – Jesus always protected his honour. In the Passion narrative, however, Jesus is seemingly shamed by both close followers and by enemies. His crucifixion has elements of honour (v. 40), however, the shame is undeniable: evident through the leaders scoffing at him (v. 35) and the presence of the criminals (v. 39). The anointing (v. 56), prayer of forgiveness (v. 43), and commitment to his father’s will as a dutiful son (v. 46) are important elements in restoring his honour.

Jesus died a shameful death, reserved for the worst of the criminals. His manner of death erased all the good he had done: if Jesus was truly beloved of God, then God would not have allowed him to be overcome by his enemies. By raising Jesus from the dead God overturns this: honouring Jesus more than anyone ever could have – obliterating Jesus’ shame. The cultural level at which Jesus is presented is as an extraordinary hero. He takes punches without flinching, endures flogging, insults, crowning with thorns, crucifixion, and all he says is “truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise” (v. 43) and “father into your hands I commend my spirit” (v. 46).

Pain and suffering:

For readers in our school communities often suffering is a nuisance and pain can be readily avoided through medicine. Jesus’ culture and beliefs were common to much of the ancient world at the time – the soul, not the body, feels pain and suffering and therefore pain and suffering can never be eliminated, only alleviated. By bearing excruciating pain and suffering in the typical ‘Mediterranean manly’ fashion, Jesus demonstrates obedience to his father. Luke seems to be concerned for consistently emphasising the deliberate response of Jesus to experience suffering. Therefore, the Passion narrative gives Western readers a chance to celebrate cultural diversity. In our culture, the significance of God being raised from the dead, being restored to honour after shame, is lost in the quest for logical meaning.

World in Front of the Text

The Passion Narrative is the oldest part of the Christian tradition to be preserved. Paul reports Christ died for our sins, was buried, raised on the third day, appears to Cephas and then to the Twelve (1 Cor 15:3b-5). Christians see the death of Jesus not just as a human story, but as the act of God himself: giving himself to save his people “God demonstrates his own love in this: while we were sinners Christ died for us” (Rom 6:8).

When troubles, hardship, and adversity arise it can test our resilience and our faith. Jesus demonstrates though, that even in the most difficult of situations we can turn to God in prayer, we can trust in God’s plan for us. Choosing to turn (or return) to God is how we build our spiritual muscles.

Christ’s willingness to accept his father’s will is something we can strive for today in our own lives. Bearing excruciating pain and suffering, to his last breath, Jesus is fully committed to the plan God has laid out for him. In our own lives we can be quick to question God’s plan for us, particularly if things aren’t turning out the way we had hoped. Jesus can guide us to live as God intended us to.

Liturgical usage:

Lent and Holy Week: The Passion narratives are central to the liturgical seasons of Lent and Holy Week in the Catholic Church. They are read and meditated upon during Palm Sunday, Holy Thursday (Last Supper), Good Friday (Passion and Crucifixion), and Easter Vigil (Resurrection).

Stations of the Cross: The Stations of the Cross, a devotional practice in the Catholic tradition, narrate the events of Jesus’ Passion and encourage personal reflection on the meaning and significance of his suffering and death.

The Eucharist: The institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper is foundational to the Catholic tradition.