11Then Jesus said, “There was a man who had two sons. 12The younger of them said to his father, ‘Father, give me the share of the property that will belong to me.’ So he divided his property between them. 13A few days later the younger son gathered all he had and travelled to a distant country, and there he squandered his property in dissolute living. 14When he had spent everything, a severe famine took place throughout that country, and he began to be in need. 15So he went and hired himself out to one of the citizens of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed the pigs. 16He would gladly have filled himself with the pods that the pigs were eating; and no one gave him anything. 17But when he came to himself he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired hands have bread enough and to spare, but here I am dying of hunger! 18I will get up and go to my father, and I will say to him, “Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; 19I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me like one of your hired hands.” ‘ 20So he set off and went to his father. But while he was still far off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion; he ran and put his arms around him and kissed him. 21Then the son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and before you; I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’ 22But the father said to his slaves, ‘Quickly, bring out a robe—the best one—and put it on him; put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. 23And get the fatted calf and kill it, and let us eat and celebrate; 24for this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found!’ And they began to celebrate.

25“Now his elder son was in the field; and when he came and approached the house, he heard music and dancing. 26He called one of the slaves and asked what was going on. 27He replied, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed the fatted calf, because he has got him back safe and sound.’ 28Then he became angry and refused to go in. His father came out and began to plead with him. 29But he answered his father, ‘Listen! For all these years I have been working like a slave for you, and I have never disobeyed your command; yet you have never given me even a young goat so that I might celebrate with my friends. 30But when this son of yours came back, who has devoured your property with prostitutes, you killed the fatted calf for him!’ 31Then the father said to him, ‘Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. 32But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.’ “New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright © 1989, 1993, 1995 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

What to do with this educator’s commentary

This commentary invites you as a teacher to engage with and interpret the passage. Allow the text to speak first. The commentary suggests that you ask yourself various questions that will aid your interpretation. They will help you answer for yourself the question in the last words of the text: ‘what does this mean?’

This educator’s commentary is not a ‘finished package’. It is for your engagement with the text. You then go on to plan how you enable your students to work with the text.

Both you and your students are the agents of interpretation. The ‘Worlds of the Text’ offer a structure, a conversation between the worlds of the author and the setting of the text; the world of the text; and the world of reader. In your personal reflection and in your teaching all three worlds should be integrated as they rely on each other.

In your teaching you are encouraged to ask your students to engage with the text in a dialogical way, to explore and interpret it, to share their own interpretation and to listen to that of others before they engage with the way the text might relate to a topic or unit of work being studied.

Structure of the commentary:

Text & textual features

Characters & setting

Ideas / phrases / concepts

Questions for the teacher

The world in front of the text

Questions for the teacher

Meaning for today / challenges

Church interpretations & usage

The World Behind the Text

There are two ‘worlds’ behind the text: the world that produced it and the world of the time in which it is set.

The world of the author’s community

Scholars generally agree that the Gospel according to Luke was written in Greek some 50 years after the death of Jesus, probably in the 80s. Tradition has given the name of Luke to the author, but there is no certainty that Luke was the author’s name. Luke may have been a Syrian from Antioch. Most scholars conclude from elements in the Gospel that the author was a Gentile writing for a community predominantly made up of Gentile Christians. More details about the Gospel according to Luke can be found HERE.

The Gospel of Luke is a testimony of faith in Jesus from and for the Lukan community. While there is a specific audience for the text named in the Gospel, the evangelist is also addressing members of his faith community, instructing them on the qualities of a disciple of Jesus. The evangelist included this parable after two others with similar themes to amplify his theological intent. This does not mean that Jesus told these three parables one after the other in their original settings.

The evangelist indicates that he is not an eyewitness to the events set out (Lk1: 1-4). Therefore, the world of the author’s community is in a different cultural setting to that of Palestine and is over 50 years after the time in which the passage is set.

Jesus told this parable to Jews in Palestine. The evangelist recounts the parable for a Gentile Christian community. The change of audience from Jews to Gentile followers of Jesus outside Palestine means that it was likely to have been understood by two audiences in different ways.

This passage is only found in Luke. This means that it comes from an oral or written source to which Luke had access but that the other evangelists presumably did not.

The world at the time of the text

Property and inheritance

In Jewish inheritance practice sons shared their father’s inheritance after he died. The oldest son received a double share and succeeded as head of the family. An ageing father could distribute the assets early, but the beneficiaries could not dispose of them until after his death.

Honour and shame

Honour was a fundamental social value in first century Palestine. A person who acted in the way that was expected was considered honourable and was held in esteem in the eyes of the social group. If someone did not follow the rules and expectations of the family, village or wider culture he or she was shamed. For certain shameful acts the village might conduct a public disgrace ceremony by shattering a large pot in front of the person as a sign that the individual was now cut off from the family and the village.

Parallels in the Jewish Scriptures

There are parables in the Hebrew Scriptures and the listeners (the Pharisees and scribes) would have been familiar with them. Examples include Jotham’s parable about the trees (Judg 9:7-15), Nathan’s condemnation of David through the parable of the lamb (2 Sam 12:1-7), and Ezekiel’s parable of the two eagles and the vine (Ezek 17: 1-9).

The story plays on the listeners’ knowledge of the Torah stories of brothers, especially of two brothers in which the younger or youngest prosper in comparison to the older one(s), including in the gaining their father’s favour and inheritance. Isaac is favoured over Ishmael; Jacob is blessed instead of the elder Esau; Joseph eventually flourishes ahead of his elder brothers; and David, the youngest of seven becomes king.

Geography

Specific geographical knowledge is not important for the comprehension of this text. The author places the text within Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem. In the parable it is clear contextually that the family lives somewhere in Jewish Palestine. The younger son journeys ‘to a distant country’ to non-Jewish territory as is evident from the reference to pigs. (Jews were forbidden to raise pigs and archaeological studies verify the absence of pigs in Palestine at the time of Jesus).

The world of the text

Before proceeding you need to read the fuller context of the parable below:

15 1Now all the tax-collectors and sinners were coming near to listen to him. 2And the Pharisees and the scribes were grumbling and saying, ‘This fellow welcomes sinners and eats with them.’ 3So he told them this parable:

4‘Which one of you, having a hundred sheep and losing one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness and go after the one that is lost until he finds it? 5When he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders and rejoices. 6And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and neighbours, saying to them, “Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.” 7Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous people who need no repentance.8‘Or what woman having ten silver coins, if she loses one of them, does not light a lamp, sweep the house, and search carefully until she finds it? 9When she has found it, she calls together her friends and neighbours, saying, “Rejoice with me, for I have found the coin that I had lost.” 10Just so, I tell you, there is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents.’

11Then Jesus said, “There was a man who had two sons …

Text & textual features

A Parable

The text is a parable, a distinct literary form. A parable is a short story designed to convey a lesson or a religious truth through similes, metaphors or vivid imagery. It draws on images from everyday activities. It invites the audience to reflect on their behaviour. Common features of parables include repetition, contrast, reversal of expectations, the frequent use of three characters or incidents, and a climax built around the last character in the series. This parable generally has those features.

Three parables of lost and found

The three parables in Luke 15 are a tightly constructed literary unity with the same themes. In each parable there is an owner, something owned, something lost, someone searching or waiting for the lost, the lost is found, and so there is excessive rejoicing and an extravagant communal celebration. The shepherd and the woman come from the bottom of social ladder but the wealthy, landowning father is the social equal of the scribes and Pharisees to whom Jesus addresses the three parables. However, irrespective of their social standing, all three celebrate the return of the lost. That is Jesus’ (and Luke’s) point.

Structure of this parable

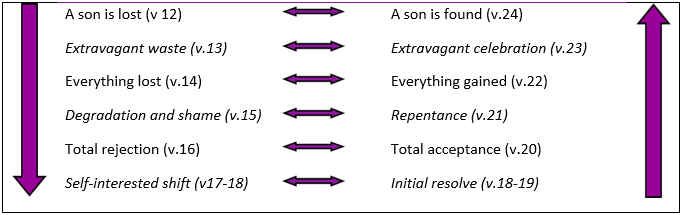

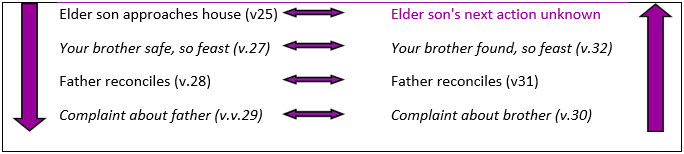

The parable of the father and his sons, the longest in all the Gospels, has two parts with similar literary structures. In the first part there are twelve steps made up of two sets of six that match each other in inverted parallelism. The second part appears to be headed for a double set of four steps. The pivot of each part is what each son says: the younger son’s soliloquy showing his realisation of being lost and the elder son’s airing his grievances. The second part is missing the final step. The parable leaves the reader to wonder about the anticipated next action by the elder son.

Typical Lukan themes

The parable has many of the themes characteristic of the Gospel of Luke: the compassion and forgiveness of the father, the acceptance an outsider, the sense of reversal so evident in the Song of Mary (Luke 1:46-55) and the Beatitudes and Woes (Lk 6: 20-26), and the joy that permeates the Gospel.

Characters & setting

The audience

Luke sets the three parables as Jesus’ responses to the grumbles of his opponents, the Pharisees and scribes who object to Jesus’ doubly offensive behaviours: he not only preaches to tax collectors and sinners, he actually eats with them. The parables justify Jesus’ behaviour: they are about recovering the lost, just as Jesus welcomes and eats with the tax collectors and sinners who count as the lost. The parables also are an invitation to Pharisees and scribes to rejoice when the lost are found and to join the celebration. For the Pharisees and scribes the lost son equates to the tax collectors and the sinner. Jesus presents the elder son as like them, obedient to their obligations but critical of those on the margin. The abrupt end of the parable asks for introspection and a change of heart by the original hearers: will you, Pharisees and scribes also come to the celebration with your ‘brothers’, the tax collectors and sinners?

The setting of the parable

The setting is the community of a village, not an isolated household on farmland. Farmers did not live on their land but lived in the close-knit village community made up of family, and other kin and neighbours. The whole village would have witnessed the story unfolding.

The father

The actions of the father conflict with the social expectations of the head of an ancient Middle Eastern family. While not forbidden to do so, the father’s early division of his property is irregular and would have been considered as weakness. The younger son effectively has severed the relationship, but the parable suggests that the father has been continually on the watch for his return. The father not only goes out to meet him, but he runs, an action that would be considered undignified. Some suggest that his motivation was to indicate his public reacceptance of the son before the people of the village could conduct the public disgrace ceremony. The father kisses the unclean son, gives him a garment of dignity, a ring that enables him to transact family business, and sandals (as servants generally went barefoot). Next he takes his prime market produce and calls a celebration, presumably for the whole village (as a fatted calf would feed dozens of people). By giving a party for the village, the father doubly ensures that there can be no ceremony of public disgrace. He continues his irregular behaviour by leaving his place at the head of that feast to plead with his elder son and tolerates his shameful insult. Through these extravagant actions the father sacrifices his honour to bring his family together.

The younger son

The first hearers of the parable may have anticipated positive things from the younger son just as had been the case with Israel, Jacob, Joseph and David. The initial characterisation would have disgusted them. The son asks for his share of the inheritance, implying that he wishes his father were dead. He sells his share in defiance of the cultural norm. He goes to Gentile territory where he cannot practise his religious obligations. He squanders his property and suffers the ultimate indignity for a Jew, that of feeding pigs. His behaviour is utterly shameful.

He ‘comes to his senses’ out of pure self-interest, not repentance. However, he still considers himself as son and rehearses his speech and addresses his father as father. He returns seeking to be a hired hand. If he can earn enough to pay back what he has squandered, he may be able to restore some of his honour. His intended words about his unworthiness reflect the honour code. When it comes time to give his prepared speech, the text leaves out ‘treat me like one of your hired hands’. Does the father interrupt him as is often presumed? Perhaps the son deliberately leaves it out because, overwhelmed by the father’s welcome and forgiveness, he recognises his restored relationship and only then repents. He acknowledges that he has sinned, accepts his reinstatement and enters the feast.

The elder son

The listeners at first would have sided with the older brother over the younger. On the surface, he is obedient and hardworking and therefore worthy. His relationship with the father up to now is unclear; one wonders why a slave had not been sent to inform him of his brother’s return so that he could take up a first-born son’s traditional role of receiving people at the door. He shames himself and grossly insults his father by refusing to go in; he makes it worse by not addressing him as his father; he denies his brotherhood by referring to the younger as ‘this son of yours’. Furthermore, he does not even think of himself as a son but has been working ‘like a slave’. He would have inherited everything since his brother left but he is irritated that he cannot use his property at will to celebrate with his friends. In one sense he is like the younger son was originally, implying that he wishes his father were dead. He rejects his father’s words of reconciliation. In this quarrel he publicly humiliates his father.

Ideas/ phrases/ concepts

Repentance?

The initial listeners may have received the parable as a story of family reunion rather than of repentance and forgiveness. The younger son does not explicitly state real sorrow; nevertheless, he returns, and the father reinstates him. However, in Luke’s design and to the ears of his Christian community, the parable is one of three that rejoice in restoration. In the first two the rejoicing in heaven is over ‘one sinner who repents’. For Luke’s audience the return of the son serves as a metaphor for ‘one sinner who repents’ and the father’s extravagant actions point to God, the forgiving father.

Son/ hired servant

The distinction between a son and a hired servant/slave is a key literary device in the narrative. The younger son leaves his father’s house, becomes the hired servant of a Gentile, still considers himself as son, seeks to become a hired servant of his father, confesses unworthiness, has his sonship restored and re-enters his father’s house. On the other hand, the elder son stays at home, claims worthiness, feels like a slave, does not consider himself a son, has his sonship confirmed but refuses to enter his father’s house.

Who is lost?

The two sons are so alike. Both dishonour the father and themselves and both end up in a far country, one physically, the other spiritually. They differ only in their responses to the father’s love. One returns and responds, and so was ‘lost and found’. As far as we know, the other remains lost.

Questions for the teacher:

The world in front of the text

Questions for the teacher:

Please reflect on these questions before reading this section and then use the material below to enrich your responsiveness to the text.

Meaning for today/ challenges

The parable is about the extravagance of God’s love and forgiveness. John McKinnon comments that it gives wonderful insights into the heart of God:

Effectively Jesus was teaching that God’s forgiveness was wild and beyond reason, shameless and irresponsible, unconditional and uncaused, spontaneous but profound, motherlike and fatherlike, life-giving and freeing, irrepressible and celebratory.

In the parable Jesus is addressing the religious elites. He wants them to understand that including the downcast in no way reduces God’s love for them. The parable also addresses us. It is not just about God’s forgiveness of sinners but about our treatment of ‘sinners’ and the marginalised. Which feast are you refusing to join? The parable invites us to finish the unfinished story by drawing close to those we may be tempted to exclude in our family, our workplace or in wider society.

Parables reverse expectations. The younger son does not deserve reinstatement. Many people sympathise with the older brother and resent how the younger brother is let off lightly. There is some part of each person in each of the three characters. With which one do you most identify?

The parable also reminds us of a profound truth in Catholic teaching. We need God’s grace to turn to God. We cannot do it entirely by ourselves. The younger son had a self-serving plan as we do so often, but God ‘runs’ to us, embracing us with the grace to enable our repentance.

Absence of the mother

Today’s reader feels very uncomfortable with the absence of the mother. Some wonder if she had died. The more likely reason is the highly patriarchal world behind the text. Inheritance and property were the domain of the males in the family; females were excluded; and so, there would be no role for the mother to play. Our world is different, and this draws us to ponder the extent of any barriers for women in contemporary economic exchange.

Of the many representations of the parable in the history of art, the 17th century ‘The Return of the Prodigal’ by Rembrandt has a tender depiction of the father. The focal point is his hands. The left is larger and masculine, and the right is softer and feminine. The spiritual writer, Henri Nouwen commented:

The father is not simply a great patriarch. He is mother as well as father. He touches the son with a masculine hand and a feminine hand. He holds, and she caresses. He confirms and she consoles. He is indeed God, in whom both manhood and womanhood, fatherhood and motherhood are fully present

The Return of the Prodigal (1992) London: DLT, p.94

A brief explanation of other features of the painting (which suffers from an erroneous reference to the Gospel of Mark) is HERE.

Church interpretation & usage

The name of the parable

Giving a parable a name pre-empts the meaning a reader may find in it. Traditionally, this parable has been called the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Prodigal means recklessly wasteful or extravagant. This has resulted in the longstanding tendency to concentrate on the younger son. However, the father is really the central figure and there are two sons, so ‘the prodigal son’ is an incomplete title. Traditionally, the two preceding parables are called ‘the Lost Sheep’ and the ‘Lost Coin’, so that implies the ‘Lost Son’; or it could be the ‘Lost Sons’. Surely any title should acknowledge the Father, for example, the ‘Forgiving Father’ or ‘the Extravagant Father’. Perhaps the simplest name that does not prescribe a meaning is simply ‘the Father and Two Sons’. What do you think?

Significance in the Christian tradition

This is one of most well known and loved of the parables. Brendan Byrne calls it one of the Gospel passages “that have truly shaped Christian identity”. Without this parable – as also perhaps without that of the Good Samaritan – Christianity would be something different.” (p.142)

The parable has been used through the centuries as an exposition on repentance and forgiveness. It has a long catechetical association with Sacrament of Penance. The father is identified with God and the younger son with the penitent sinner. Recent years have seen proper consideration of the elder son whose characteristics are in each of us. Some earlier interpretations identifying him with Jews misrepresent the text.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church, n.1439 uses it to explain conversion and repentance:

The process of conversion and repentance was described by Jesus in the parable of the prodigal son, the centre of which is the merciful father: The fascination of illusory freedom, the abandonment of the father’s house; the extreme misery in which the son finds himself after squandering his fortune; his deep humiliation at finding himself obliged to feed swine, and still worse, at wanting to feed on the husks the pigs ate; his reflection on all he has lost; his repentance and decision to declare himself guilty before his father; the journey back; the father’s generous welcome; the father’s joy – all these are characteristic of the process of conversion. the beautiful robe, the ring, and the festive banquet are symbols of that new life – pure worthy, and joyful – of anyone who returns to God and to the bosom of his family, which is the Church. Only the heart of Christ Who knows the depths of his Father’s love could reveal to us the abyss of his mercy in so simple and beautiful a way.

Pope St John Paul II used it to explain God’s mercy in his encyclical Rich in Mercy (1980) n.5-6. The merciful father concentrates on the humanity and dignity of his lost son and “the genuine face of mercy has been revealed anew”. In Reconciliation and Penance (1984) n.5-6, he states that the prodigal son is every human being, bewitched by the temptation to be separated from God. The father’s festive and loving welcome is a sign of God’s mercy. Every human being is also the elder son, in our jealousy, hardened hearts, and separation from others and God. This expresses the selfishness of the human family and the need for profound transformation of hearts through the discovery of God’s mercy.

Liturgical use

The text is the Sunday Gospel on two occasions in Year C. They are the Fourth Sunday of Lent for its penitential significance, and the 24th Sunday in Ordinary Time, as part of the progressive movement through the Gospel of Luke in Year C. The text also is one of a wide range of options for the Celebration of the Sacrament of Penance.