17 He came down with them and stood on a level place, with a great crowd of his disciples and a great multitude of people from all Judea, Jerusalem, and the coast of Tyre and Sidon. 18 They had come to hear him and to be healed of their diseases; and those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured. 19 And all in the crowd were trying to touch him, for power came out from him and healed all of them.

New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition, copyright © 1989, 1993 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

20 Then he looked up at his disciples and said:

“Blessed are you who are poor,

for yours is the kingdom of God.

21 “Blessed are you who are hungry now,

for you will be filled.

“Blessed are you who weep now,

for you will laugh.

22 “Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Son of Man. 23 Rejoice in that day and leap for joy, for surely your reward is great in heaven; for that is what their ancestors did to the prophets.

24 “But woe to you who are rich,

for you have received your consolation.

25 “Woe to you who are full now,

for you will be hungry.

“Woe to you who are laughing now,

for you will mourn and weep.

26 “Woe to you when all speak well of you, for that is what their ancestors did to the false prophets.

What to do with this educator’s commentary

This commentary invites you as a teacher to engage with and interpret the passage. Allow the text to speak first. The commentary suggests that you ask yourself various questions that will aid your interpretation. They will help you answer for yourself the question in the last words of the text: ‘what does this mean?’

This educator’s commentary is not a ‘finished package’. It is for your engagement with the text. You then go on to plan how you enable your students to work with the text.

Both you and your students are the agents of interpretation. The ‘Worlds of the Text’ offer a structure, a conversation between the worlds of the author and the setting of the text; the world of the text; and the world of reader. In your personal reflection and in your teaching all three worlds should be integrated as they rely on each other.

In your teaching you are encouraged to ask your students to engage with the text in a dialogical way, to explore and interpret it, to share their own interpretation and to listen to that of others before they engage with the way the text might relate to a topic or unit of work being studied.

Structure of the commentary:

Text & textual features

Characters & setting

Ideas / phrases / concepts

Questions for the teacher

The world in front of the text

Questions for the teacher

Meaning for today / challenges

Church interpretations & usage

The World Behind the Text

See general introduction to Luke.

Scholars generally agree that the Gospel according to Luke was written in elegant Greek some 50 years after the death of Jesus, probably in the 80s. The Gospel is the first of two works by the author, its companion volume being the Acts of Apostles. Tradition has given the name of Luke to the author, but there is no certainty that Luke was the author’s name, and if it was, that he was the Luke mentioned in the Acts of Apostles and the Letters of Paul. Luke may have been a Syrian from Antioch. Most scholars conclude from elements in the Gospel that the author was a Gentile writing for a community predominantly made up of Gentile Christians. More details about the Gospel according to Luke can be found HERE.

Each Gospel is a testimony of faith originating out of a Christian community. The author reflects the concerns and issues of the community. In Luke’s predominantly Gentile Christian community, it is likely that the material wealth of some of its members, the poor among and around them and questions of wealth and poverty were issues of debate. These concerns are a characteristic of the Gospel in general and this text in particular.

The world of the text

The situation of the text is early in Jesus’ public ministry in rural Galilee. It was a society of very sharp social boundaries and a large gulf between the poor and the rich. Most rural people were poor agricultural peasants. They lived at a subsistence level, frequently in danger of hunger or starvation if the crops failed. Roman rule also marginalised them. They were forced to pay high taxes on what they earnt. The wealthy – urban and temple elites and landowners – were a small proportion of society and benefited from land rent and civil and religious taxes.

In addition to the material poverty, many may have associated reference to the poor with the “poor ones” who remained faithful to God in times of difficulty. These humble people were known in Hebrew as the anawim or the “faithful remnant” of Israel.

Jewish people at the time of the text would have been aware of the blessings found in the Hebrew Scriptures, eg, in the Psalms (Ps 1; Ps 112). At other places blessings are accompanied by curses. In texts about God’s covenant and the delivery of the Torah through Moses such as Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28 there blessings for fidelity and curses for infidelity to the covenant. These also were the foundations for the oracles (or divine messages) through the prophets. Their oracles were either imminent realisation of curses for being unfaithful to the covenant or future blessings of covenant fulfilment. Examples can be found in Isaiah chapters 13 – 23.

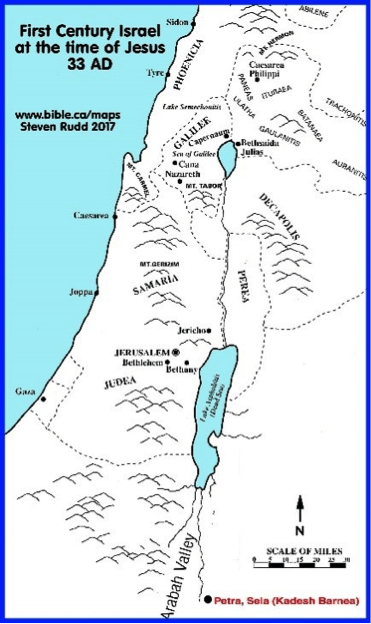

Geography

The text is set in Galilee in the northern part of the provinces of first-century Palestine. To the south was Judea and its capital, Jerusalem. The inhabitants of Judea were mainly Jews. Galilee also had a large Jewish population but also had many who were not Jewish. Further north on the Mediterranean coast were the cities of Tyre and Sidon in Phoenicia (part of modern Syria). Most of their population was not Jewish. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the multitude consisted mainly of Jews but also of gentiles.

Text & textual features

This passage is the start of a sermon which runs for the rest of the chapter. It is frequently referred to as the Sermon on the Plain due to its setting on level ground and its parallels with Matthew’s longer Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5-7).

Though the writer presents the teachings as a single address, they are more likely to have been presented at various times and places.

The similarity of Luke’s blessings with four of Matthew’s, along with their absence in Mark, leads most scholars to suggest that the common source is Q (See Synoptic Problem).

It is important to see the text in relation to what precedes and what follows in the rest of the sermon. The writer places the passage after three other key happenings. In v.12 Jesus prays on a mountain all night. In vv. 12-15 Jesus chooses from among the disciples, the twelve whom he names apostles. After coming down he responds to the afflicted multitudes and in vv.18-19 he heals ‘all of them’. Having modelled the prayer and compassionate actions he expects of his followers he puts them into words. The Beatitudes and Woes are challenging enough but Jesus goes further. He goes on to present his cornerstone teaching of love of enemies, the requirement to be merciful (or compassionate) and not to judge others.

In the Gospel of Matthew Jesus commences his Sermon on the Mount with a set of nine blessings. Luke’s version is expressed more succinctly than that of Matthew. In comparison, Luke’s is stark, blunt, concrete and unqualified. The Lukan version gives four blessings and a matching set of four woes. They are written in the second person, that is to ‘you who are poor’.

The literary form of the blessings and woes recall those of the covenant and of the prophetic oracles.

The text amplifies a key theme of the whole Gospel. In the synagogue at Nazareth Jesus proclaimed his mission to bring good news to the poor (Luke 4:18-18). Luke had introduced this message in Mary’s song of praise about God who lifts up the lowly, fills the hungry with good things, scatters the proud, brings down the powerful and sends the rich away empty (Luke 1:46-55).

Characters & setting

Matthew’s setting for the teaching is a mountain. A mountain had been the site of Moses’ encounter with God. Luke situates the scene on level ground. Echoes of Moses would not arouse the same instinctive reactions in Luke’s gentile community as it in Matthew’s formerly Jewish one.

It is worth reflecting on who is the audience. Jesus looks ‘up to his disciples’ and gives them his first instructional teaching. However, he wants others to listen and hear, and for his disciples to know they are. The ‘great multitude’ are the burdened and afflicted who have sought and received Jesus’ healing power. They are the poor. If the disciples are to be students of Jesus, as the word disciple means, like Jesus they must bring good news to the poor. The ‘great multitude’ also denotes that this message is for everyone. In fact, this is the first time in this Gospel that Jesus teaching goes outside the Jewish people, as most people from Tyre and Sidon are gentiles.

Are there rich people among the listeners or among the disciples? Possibly so, since there is a great multitude. It is more likely that the audience for the written text, Luke’s own community includes some people of material wealth living in the midst of poverty. The writer has Jesus directly addressing the woes to them – “you who are rich” – and to other would-be followers who have possessions, instructing that the self-sufficiency of wealth, its associated benefits and being held in high regard interferes with discipleship of Jesus. He goes on to state later that they must share their wealth with the needy “expecting nothing in return” (verses 34-36).

Ideas/phrases/concepts

Blessing and woe

The Gospel was written in Greek. The Greek word makarios is used in the blessings. The closest translation is Congratulations! The Greek word used for woe is ouai, an expression of denunciation of something or someone as blameworthy and can imply impending calamity as a result.

The poor and the rich

The first three blessings and woes all refer to the same people. The key distinction here is between the ‘poor’ and the ‘rich’. The ‘poor’ also are hungry and they weep, and they are reviled.

The poor are blessed because God takes their side. The blessing is immediate: they can experience God’s reign here and now (‘yours is the kingdom of God’). The fullness of life for which they long, however, belongs to the future. By contrast, the consolation and benefits of the rich is restricted to the present. In the future they will be hungry, mourn and weep. The sayings present a particular image of God, one who reverses how things are and preferences the poor, just as was stated in Mary’s song of praise.

The evangelist does not spiritualise the poor like the writer of Matthew does (“the poor in spirit”; “hunger and thirst for righteousness”). The insistence on literal material poverty here cannot be explained away. Typical of the whole of this Gospel, the Kingdom is linked to the practice of social justice here and now.

However, the Lukan text should not be used to set up a dichotomy between material and spiritual poverty. Brendan Byrne explains it this way:

[It] is often asked whether by the “poor” who are blessed by God Luke means the economically poor or the spiritually poor. The whole pattern of Luke’s Gospel suggests that the question poses a false alternative. The “poor” certainly are the economically poor; the Beatitudes, like the Magnificat of Mary, cannot be spiritualised away so as to have no bearing upon economics or social justice. At the same time, in Jesus’ day the “poor” had become a standard self-description for the faithful in Israel who wait hopefully upon the Lord… At the heart of their waiting for salvation – salvation in the total sense, including economic and structural salvation – lies a deep spiritual longing … In this perspective “the poor” can include the afflicted in general, whatever the cause or nature of the affliction they suffer. “The poor” are all whose emptiness and destitution provide scope for the generosity of God.

Therefore, ultimately because of their utter dependence on God, the poor are blessed. The woes are not divine hatred against the rich, but rather God’s displeasure with the oppression which they cause and their arrogant disregard of God. The rich long for wealth and not for God and neglect or exclude the poor, and therefore they are rejected with the prophetic ‘woe’.

Kingdom

Jesus preaches “the good news of the kingdom of God” (Lk 4:43). It is the great theme of his teaching in Luke and the other Gospels. The term appears 39 times in Luke. It is the restoration of God’s dream for the world, a new age of God’s life-giving rule over all creation. As noted above, in the Lukan view it is a reversal of the injustice in this world and salvation in the next. An emphasis in this Gospel is that the Kingdom is open to all the poor of God, Jews and gentiles alike. The timing of the Kingdom is elusive: it is here “among you” (Lk 17:20-21); it is “near” (Lk 10:11); but the disciples are to pray for its coming (Lk 11:2) and Jesus tells a parable “because they supposed that the Kingdom of God was to appear immediately” (Lk 19:11).

Questions for the teacher:

The world in front of the text

Questions for the teacher:

Please reflect on these questions before reading this section and then use the material below to enrich your responsiveness to the text.

Meaning for today/ challenges

There may not be a Gospel passage more challenging than this. It raises the question of our ultimate goal in life. We naturally and rightly desire success, comfort and wellbeing but Jesus states that these are secondary to self-giving to others. The rich are not condemned for their success and comfort but because they are indifferent to the poor and do not share their good fortune. Following Jesus requires a change in perspective and action from self-sufficiency to awareness of our dependence on God and to our co-responsibility for others, especially the poor and marginalised.

The passage is part of a sermon directed at the disciples and in the hearing of the multitude. Our reflection on the text is calls us to move from being simply part of a multitude to be more fully a disciple of Jesus, one who learns from and imitates him.

Church interpretation & usage

The Church traditionally has organised its moral instruction around the Ten Commandments and the Catechism of the Catholic Church continues this practice. The Beatitudes have become more significant in recent decades because of a greater dependence on Scripture in moral discourse, stress on the total Christian life not just its minimum requirements, and the stronger emphasis on the social mission of the Church.

The Beatitudes and the Sermon on the Mount give the fullest expression of Christian morality. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that they “are at the heart of Jesus’ preaching” (n.1716) and “reveal the goal of human existence, the ultimate end of human acts” (n.1719) for God calls us to his own beatitude, the Kingdom, the vision of God in eternal life (n.1726). “The Beatitudes confront us with decisive choices concerning earthly goods; they purify our hearts in order to teach us to love God above all things” (n.1726).

In his apostolic exhortation Gaudete and Exsultate (‘Rejoice and Exult’) Pope Francis dedicates chapter three to the Beatitudes. He commences as follows:

Jesus explained with great simplicity what it means to be holy when he gave us the Beatitudes (cf. Mt 5:3-12; Lk 6:20-23). The Beatitudes are like a Christian’s identity card. So if anyone asks: “What must one do to be a good Christian?”, the answer is clear. We have to do, each in our own way, what Jesus told us in the Sermon on the Mount. In the Beatitudes, we find a portrait of the Master, which we are called to reflect in our daily lives.

n.63

Over the years the Church has referred to Matthew’s Beatitudes more often than to those of Luke. More recently, Catholic Social Teaching and theological discourse has made greater reference to Luke in its advocacy for social justice. Latin American Liberation Theology used the Beatitudes and Woes and the Gospel of Luke in general to advocate for a ‘preferential option for the poor’, a term taken up in the teachings of Pope St John Paul II (Centsimus Annus, 57) and his successors. Pope Francis comments that “the Church has made an option for the poor”: which,

as Benedict XVI has taught − ‘is implicit in our Christian faith in a God who became poor for us, so as to enrich us with his poverty’. This is why I want a Church which is poor and for the poor. They have much to teach us”. He goes on to state that we “need to let ourselves be evangelised by them” and “to put them at the centre of the Church’s pilgrim way.”

Evangelii Gaudium, n.198